It’s no secret to anyone who knows me that I’m a little bit of a purist (some would say a snob – and maybe, sometimes, justly) about shooting period bows and arrows in the SCA. Not to completely get up on my soapbox about it here, because this is supposed to be about arrows, but I feel the need to justify why I’m writing this, so here it is:

I feel that people doing archery in a medieval recreation society should be actually trying to do medieval archery.

That’s it.

So, to practice what I preach, I only shoot “period” bows, and I only shoot “period” arrows.

————–

Aside: I’m putting “period” in quotes because what I’m doing, and virtually everyone else shooting in the period divisions of the SCA are doing, isn’t really shooting actual period equipment. The function and form is largely correct, but:

- We aren’t at medieval draw weights. Most experienced SCA shooters are shooting between 40 and 50 pound draw weights at 28 inches. That’s a half to a third, at best, of what a medieval archer pulled.

- We’re almost all shooting bows made with modern glues and epoxies.

- Virtually every shooter of an Asiatic “horsebow” in the SCA is shooting a bow with fiberglass in it.

- Medieval arrows weren’t made from perfect dowels.

- Most longbow shooters are shooting laminated bows, made from two to four layers of different woods (including bamboo).

and so on and so forth.

—————-

Conveniently, the Society already defines what’s a “period” bow and arrows, right here, on page 13: https://www.sca.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/target_archery_rules.pdf

The broad strokes are that you need to be shooting off your hand, which means no cut-out rest in the riser (handle) of the bow – the arrow rests on your hand alone – and you need to be shooting arrows with self-nocks, that is, the nock of the arrow is cut into the shaft of the arrow, rather than being a glued-on commercially-made plastic nock. All SCA archers have to shoot wooden shafts with feather fletchings, at least, so there’s that, right?

That’s all. That doesn’t seem so hard, right?

And yet, the vast majority of archers in the SCA can’t seem to get there; they are still shooting what’s generally referred to as “traditional” archery equipment. In the before-time, pre-internet, it could be difficult to get a bow that met the period archery requirements. No one really made them outside of hobbyists, and the traditional archery scene in the USA is huge, so those types of bows are readily available – often at garage sales and secondhand shops for a near-pittance. But now that we have the internet, bows of a much more medieval form are available from a bunch of different places. Both horsebows and longbows that meet the SCA’s definition of “period”, as I discussed above, can be had for around $100, and a dozen appropriate arrows can be had for as little as $40.

Now, certainly that’s not “let’s go try out archery” money for most people. For a beginner, telling them to fork out $150 to try out archery would most likely kill their interest immediately. But I’m not trying to make the case that a beginning archer in the SCA should be shooting period gear – just like no one’s telling a fledgling fighter that they should be buying a $500 helmet before they can fight. But, just like with fighting, where when a fighter reaches a certain threshold of skill and time-in-grade, it’s time for them to surrender the ancient bascinet from the loaner pile and start looking at something that fits their own head and persona, when archers reach a certain skill and dedication level, I feel like they ought to be looking to set down their Samick Sage or their 1978 Bear recurve, and start looking to move to a period longbow or horsebow.

Why they do not, I cannot wrap my head around. (If you have an idea why, please reach out and tell me!) My current working theory is, again, availability of equipment. Availability of bows is largely a moot point now that vendors such as AliBow, Flagella Dei, Ringing Rocks Archery, and many others are selling longbows and horsebows that meet the SCA’s period requirements for very reasonable prices. However, availability of arrows may be an issue. Many, many archers in the SCA either make their own arrows, or personally know a person who is making their arrows for them, and if this is you, then you’re my target audience for this next section.

Now we get to the meat of this blog post: I’m going to show you (you being a lightly experienced fletcher, let’s say, someone who has made at least a dozen dozen arrows) how to make a simple, cheap, and plausibly period arrow from readily available, commercial components.

There are really just four parts to an arrow: shaft, nock, point, and fletchings. Let’s talk about how to make these plausibly period for each one.

The Shaft

The vast, vast majority of SCAdian arrows are made of a wood called Port Orford cedar (POC), Chamaecyparis lawsoniana: https://www.wood-database.com/port-orford-cedar/. This is a miracle wood for archery: it’s light, has a very straight grain, and is reasonably strong for it’s weight.

It’s also from Port Orford, Oregon, USA. That makes it, to me, NOT a period wood for anyone doing a European, Asian, or African persona in the SCA’s time period.

Fortunately, there are other options. While ash would be a wonderful option, ash arrow shafting isn’t really available anywhere. We do have three fine choices though: bamboo, German Spruce, and Larch (Tamarack). I’ve shot all three, and while none of them are the miracle wood POC is, they’re all straight and shootable woods. German spruce is very light, almost as light as POC. Larch is a heavier wood, but extremely tough. Every archer has had the experience of hitting something hard, like a stone or a metal fencepost holding a target, and having the point of their POC arrow snap off cleanly right at the tip. Larch just bounces off. Bamboo is light, cheap, and strong, but often needs straightening, and cutting self-nocks into hollow bamboo takes practice.

The shaft should not be striped, colored, painted, or otherwise tarted up. Avoid a super-shiny modern polyurethane coating. A simple wipe with boiled linseed oil, tung oil, or a similar natural wood finish works great. If those aren’t available, you can use poly; try the wipe-on kind in a satin finish, and don’t do more than two coats.

The Nock

In traditional archery, the nocks of arrows are made of plastic and glued onto the wood shaft. They’re cheap, clip onto the string nicely, and are perfectly consistent. They do absolutely provide a significant advantage over a medieval self-nock. But plastic nocks are definitely not period (although glue-on nocks ARE period; particularly in Turkish and middle-eastern archery both horn and wood nocks were fashioned separately from the shaft, and glued on. If you can find these – and there are some domestic distributors of them – by all means go nuts and use them). Most medieval arrows were of what we call the “self nock” variety, that is, the nock is cut directly into the shaft of the arrow. There are lots of ways to do this, and as bows got stronger and stronger, different types of reinforcements were necessary to prevent the power of the bow from instantly splitting the wood shaft upon release. Cord wraps and horn inserts were the most common in European medieval archery.

However, as I said above, most SCAdians are only shooting a 40-50 pound bow. At those weights, not much actual reinforcement is needed. The important things are to make SURE you are sawing the nock against the grain of the arrow, and put a simple cord wrap just below the nock. When I say, “saw against the grain”, I mean that if you look at the round ends of your arrow shafts, you will see parallel lines running across them. That’s the grain. You want to saw across those lines, perpendicular to them. If you saw your nocks parallel to those grain lines, your arrows are going to split on release. I promise you, arrow go boom. It’s quite scary and a bit dangerous. Best thing to do is, once you’ve located those grain lines, just use a pencil or a marker and draw a line across them, then saw the nock there.

You do have to actually saw in the nocks; usually about 1/2″ deep is how far to go. The best tool (non-motorized tool, that is) for doing this that I’ve found is three hacksaw blades taped together, with the middle blade’s teeth facing the opposite direction from the two outside blades. You can tape one end of the blades, then tape from the middle all the way to the other end and use that part as a handle.

You have to hold the shaft while doing this; for this I recommend a table vise with padded jaws. Some scrap leather will pad them fine, or you can buy magnetic nylon jaw covers for your vise online that have a V on one side that holds round shafts wonderfully. It should only take a few pulls of the saw to make the nock once you’ve got the hang of it.

You can do a LOT of shaping and futzing about with your self nocks if you want to. Some people use a round file to make the canyon rounded to fit the string better, others use a belt sander or sanding blocks to round off the ends of the dowel. I like to taper them a bit roughly on my belt sander (a $35 tool from Harbor Freight) then use a drywall sanding sponge to smooth them out.

For the wrap, you want it right below the bottom of the nock. You can use artificial sinew or thick nylon thread from a leatherworking shop, silk thread for a later period look, or (what I use) some very thin linen string I bought a big spool of.

You only need to do about 3/8″ of a wrap, then tie it off. I like to cheat here a bit with some modern materials, and use a very thin superglue to coat my wrap, and let a little of it sink into my nock as well. Makes it immeasurably stronger with little effort, and it’s almost invisible.

The Fletchings

The default feather for fletching arrows, worldwide, is now the turkey feather. It’s much like Port Orford cedar for arrow shafts; they’re miracle feathers for arrows. They’re large, long, robust, easily dyed, and readily available as a byproduct of the poultry industry.

I looked long and hard, far and wide, for an alternative to turkey feathers for fletchings, because the turkey, being a New World bird, is totally inappropriate for a “period” arrow.

You simply can’t do it. Not if you’re looking, as I am, for a readily available commercial source. Let’s go over what I tried:

- Domestic chickens and ducks have been bred for hundreds of years to have smaller flight pinions. No good.

- Raptor feathers, those of eagles, hawks, etc. are all prohibited from ownership, and all raptors are protected species. These feathers are made of unobtanium unless you are a member of a First Nation – and they’re not fletching arrows with them, they’re sacred objects used for ceremonial purposes.

- Seagulls are a protected migratory bird (yes, really) and you can’t possess any part of those.

- Ditto for Canadian geese. Never mind that you can go find a field where a thousand Canadian geese rested overnight while flying North or South and glean dozens of suitable feathers from the ground, you can’t possess those.

- Crows would work – but I’d have to hunt them myself. No one I found is selling crow feathers in any bulk. Besides, I like crows – I have a whole murder I feed peanuts to year-round in my backyard.

At that point I threw in the towel. It was turkey feathers or nothing. I had to live with it.

However, I could at least make them look more period. Pre-cut arrow fletchings these days come mostly in two shapes, “shield cut” and “parabolic”:

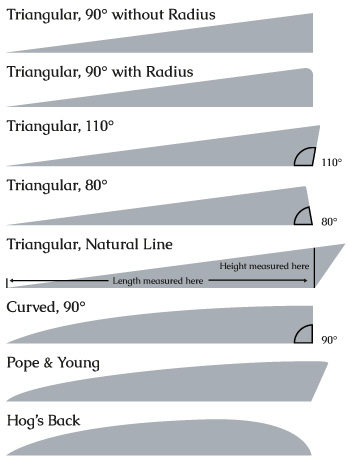

Neither of those is particularly medieval-looking. Most medieval fletchings are either cut straight down perpendicular to the shaft at the back, or have a trailing rear point. Fortunately, there’s a type of feather shape from the early days of traditional archery that, while also not readily available, at least it’s popular enough that you can buy templates to cut your own. It’s called Pope & Young (after two famous traditional archers):

Most European medieval arrows end up being one of the triangular shapes above, while Asiatic arrows tend to be fletched with a more rounded profile, more like the “Hog’s Back” fletching shown above. I find the Pope & Young shape to be a nice midpoint between the two; it has a bit of a curve on the long side, but retains the trailing rear point that’s so common. That said, I have also fletched period arrows in the 90 degree triangular shape and the “natural line” shape. They all work fine. At the ranges and skill levels most SCA archers are shooting at, we won’t see a real difference between any of the above shapes.

But, we were talking about commercially-available stuff. None of the above shapes are. Commercially available, I mean. Fear not, it’s pretty easy to cut your own, and actually cheaper as well. Here’s what you need, in addition to a bag of full-length turkey fletchings:

- Template

- Rotary cutter

- Squeeze clamp

- Cutting board

- Utility knife

You clamp the template over the feather, keeping the quill in the cut-out channel on the backside, clip off the back of the quill with the utility knife, then use the rotary cutter to cut the shape.

Take off your clamp, lift up your template, and you have a fletching. Do that 35 more times and you can fletch a dozen arrows.

When fletching, I use the same modern glues and materials I use when making traditional arrows (a lengthy pictorial primer on how I do that can be fond here: https://imgur.com/gallery/gbLql ). Again, looking for readily available. Using fish or hide glue here, and tying on the fletchings all the way down, is like a modern seamstress hand-sewing interior seams on a period garment. No one’s going to know but her, so why do it?

A final note on colors: medieval folks didn’t have blue, or yellow, or purple, or red, or green feathers. They had the colors that come on birds: white, black, brown, and gray. Please try and stick to those. Also please avoid the “barred” feathers. Not only do they cost more (because the barring is artificial) they’re meant to look like turkey feathers, and the turkey’s the bird we’re trying to pretend we’re NOT using the feathers of here. I know the temptation for SCAdians to try and bling up ALL THE THINGS is nearly irresistible, and fletching your arrows with the colors of your arms, household, or kingdom seems like a great idea… but it’s wrong.

The Point

Not much to say here. Almost any medieval point you can think of will be disallowed at an SCA archery range (and most club ranges, too) for doing to much damage to the target butts. Personally, for me, I think the standard field point is just fine for SCA use at any event.

However, if you want to go the extra mile, there are a number of modified bodkin points, or “modkins”, commercially available.

Personally, I use the TopHat screw-on modkins. They’re universally acceptable because the largest diameter of the point is no larger than the shaft of the arrow, there’s just a small hip on them for aesthetics.

Another very medieval-looking option is conical pin points:

So just install whatever points you like, and you have yourself a “plausibly period” arrow, as I have taken to calling them.

And that’s plausibly period arrows. I’ve been shooting these arrows ONLY, made from larch or German spruce, since the beginning of 2018. I am a Master Bowman with period equipment in both the recurve and crossbow categories, and I’m knocking at the door with longbow (currently shooting mid-70’s with period longbow, but ran out of daylight for practices this year). If I can do it, you can do it.

Would I probably put up higher scores shooting off the rest of a traditional recurve bow, with plastic nocks, and perfect factory-cut fletchings? Almost certainly. But I’d also put up better scores shooting an Olympic recurve, carbon fiber arrows, or a compound bow. Did you just recoil in horror at the idea of that?

Then why are you still shooting trad equipment?

-Snorri

Pretty much, yup! Asiatic feather profiles can be quite long, and low profile.

LikeLike

I have a template for some Korean medieval military feathers, the damned things are like 7″ long and don’t fit in the clamp of my Bitzenburger jig. 😦

LikeLike

And Asiatic arrows often have the cock feather on top, not to the side, may be 180/90, and may be closer to the nock.

LikeLike

For your information….the earliest archery publication translated from Medieval French in 1901 https://www.archerylibrary.com/books/gallice/

LikeLike